|

Freethought & Rationalism ArchiveThe archives are read only. |

|

|

#1 | |||

|

Contributor

Join Date: Mar 2003

Location: London UK

Posts: 16,024

|

Fascinating discussion on CEMB that is very appropriate for here.

Quote:

Quote:

Quote:

|

|||

|

|

|

|

#2 | |

|

Contributor

Join Date: Mar 2006

Location: Falls Creek, Oz.

Posts: 11,192

|

Copy editing <insert your favourite monotheistic figure head here>

We must be mindful that transmission was via "professional transcribers thoroughly practised in their art." Quote:

|

|

|

|

|

|

#3 |

|

Contributor

Join Date: Mar 2003

Location: London UK

Posts: 16,024

|

It is amusing to ask what the brain does to the words of Jibreel being whispered into the Prophet's Ear to start with!

First, is Jibreel accurately reporting Allah? Is that possible? Next, Uncle Mo has to take the holy words and recite them! Did he pick up all the influences, inflexions, nuances? And then the act of writing it down - turning voices in one's head into words, no matter how holy the specific dialect being used. Was the process similar to that of automatic writing, which anyone can learn with practice! Some of the sayings do sound like stuff straight out of a self help book! Are we actually looking at a record of how something was changed from something in one's head into writing, a possibly quite interesting neurological history? |

|

|

|

|

#4 |

|

Contributor

Join Date: Mar 2003

Location: London UK

Posts: 16,024

|

The whole process needs looking at in detail.

Allah has a thought. That is already a process of distilling everything into some form of conclusion. This must then be communicated to Gabriel, what evidence is that the angel has "got" the message, then to Mohammed, then to the followers. The Islamic chains of passing something on seem to be problematic from the beginning! |

|

|

|

|

#5 |

|

Veteran Member

Join Date: Oct 2004

Location: Bordeaux France

Posts: 2,796

|

Here is an interesting paper by Toby Lester in the Atlantic Monthly :

http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/...-koran/304024/ In 1972, during the restoration of the Great Mosque of Sana'a, in Yemen, laborers found tens of thousands of fragments from close to a thousand different parchment codices of the Koran, the Muslim holy scripture. Some of the parchment pages in the Yemeni hoard seemed to date back to the seventh and eighth centuries A.D., or Islam's first two centuries—they were fragments, in other words, of perhaps the oldest Korans in existence. What's more, some of these fragments revealed small but intriguing aberrations from the standard Koranic text. Such aberrations, though not surprising to textual historians, are troublingly at odds with the orthodox Muslim belief that the Koran as it has reached us today is quite simply the perfect, timeless, and unchanging Word of God. The first person to spend a significant amount of time examining the Yemeni fragments, in 1981, was Gerd-R. Puin, a specialist in Arabic calligraphy and Koranic paleography based at Saarland University, in Saarbrücken, Germany. The prospect of a Muslim backlash has not deterred the critical-historical study of the Koran, as the existence of the essays in The Origins of the Koran (1998) demonstrate. Even in the aftermath of the Rushdie affair the work continues: In 1996 the Koranic scholar Günter Lüling wrote in The Journal of Higher Criticism about "the wide extent to which both the text of the Koran and the learned Islamic account of Islamic origins have been distorted, a deformation unsuspectingly accepted by Western Islamicists until now." In 1994 the journal Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam published a posthumous study by Yehuda D. Nevo, of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, detailing seventh- and eighth-century religious inscriptions on stones in the Negev Desert which, Nevo suggested, pose "considerable problems for the traditional Muslim account of the history of Islam." That same year, and in the same journal, Patricia Crone, a historian of early Islam currently based at the Institute for Advanced Study, in Princeton, New Jersey, published an article in which she argued that elucidating problematic passages in the Koranic text is likely to be made possible only by "abandoning the conventional account of how the Qur'an was born." And since 1991 James Bellamy, of the University of Michigan, has proposed in the Journal of the American Oriental Society a series of "emendations to the text of the Koran"—changes that from the orthodox Muslim perspective amount to copyediting God. |

|

|

|

|

#6 |

|

Veteran Member

Join Date: Oct 2004

Location: Bordeaux France

Posts: 2,796

|

Two early Kufic manuscripts survive.

One is a codex popularly known as the "Samarqand" codex as it is said to have first come to this city about 1485 AD and to have remained there until 1868. It was removed to St. Petersburg and in 1905 fifty facsimile editions were prepared by one Dr. Pisarref at the instigation of Czar Nicholas II under the title Coran Coufique de Samarqand, each copy being sent to a distinguished recipient. In 1917 it was taken to Tashkent where it now remains. Not more than about a half of this manuscript survives. It only begins with the seventh verse of Suratul-Baqarah and many intervening pages are missing. The whole text from Surah 43.10 has been lost. What remains, however, indicates that it is obviously of great antiquity, being devoid of any kind of vocalisation although here and there a diacritical stroke has been added to a letter. Nonetheless it is clearly written in Kufi script which immediately places it beyond Arabia in origin and of a date not earlier than the late eighth century. No objective scholarship can trace such a text to Medina in the seventh century. Its actual script is very irregular. Some pages are neatly and uniformly copied out while others are distinctly untidy or imbalanced. On some pages the text is fairly smoothly spread out while on others it is severely cramped and condensed. The other famous manuscript is known as the "Topkapi" codex as it is preserved in the Topkapi Museum in Istanbul in Turkey. Once again, however, it is written in Kufi script, giving its date away to not earlier than the late eighth century. Like the Samarqand codex it is written on parchment and is virtually devoid of vocalisation though it, too, has occasional ornamentation between the surahs. It also appears to be one of the earliest texts to have survived but it cannot sincerely be claimed that it is an `Uthmanic original. The Topkapi codex has eighteen lines to the page while the Samarqand codex has between eight and twelve. The whole text of the former is uniformly written and spaced while the latter, as mentioned already, is often haphazard and distorted. They may well both be two of the oldest sizeable manuscripts of the Quran surviving but their origin cannot be taken back earlier than the second century of Islam. The oldest surviving texts of the Quran, whether in fragments or whole portions, date not earlier than about a hundred and fifty years after the Prophet's death. |

|

|

|

|

#7 | |

|

Contributor

Join Date: Mar 2006

Location: Falls Creek, Oz.

Posts: 11,192

|

Quote:

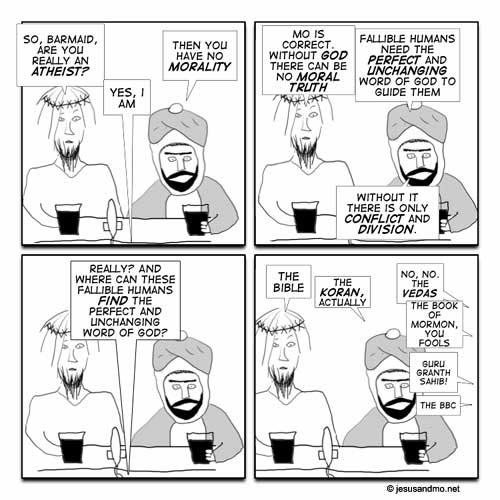

OMG. Big E. had the same problem.  http://www.jesusandmo.net/2006/01/16/word/ |

|

|

|

| Thread Tools | Search this Thread |

|