|

Freethought & Rationalism ArchiveThe archives are read only. |

|

|

#1 | |

|

Veteran Member

Join Date: Jan 2006

Location: London, Ontario, Canada

Posts: 1,719

|

I thought it might be useful to consider how much of "Astrotheology" we can see in various ancient mythologies, the idea being that we can then see how Christianity fits into the picture: does it have more, less, or the same amount of astrotheology as other mythologies?

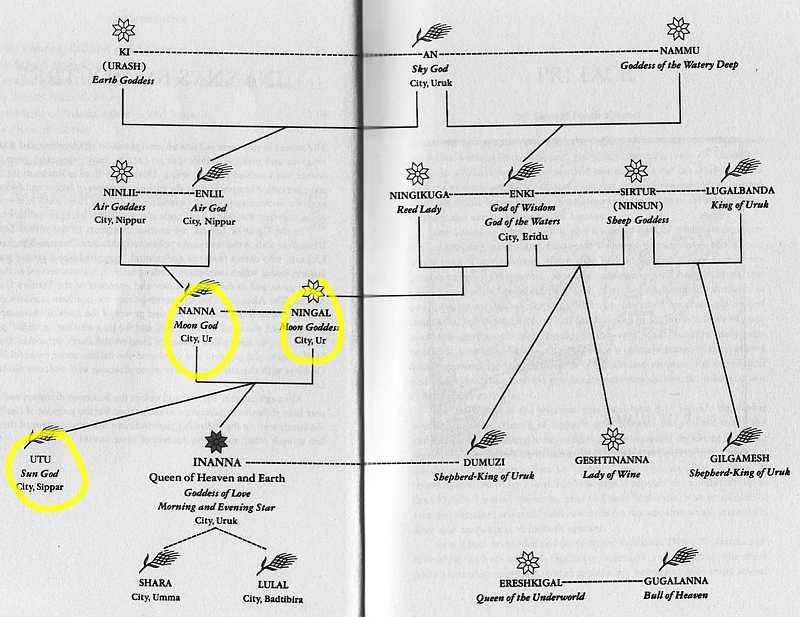

I will make a start with Mesopotamian mythology, hopefully leaving different mythologies to others. The following is mostly based on two books: Inanna by Wolkstein and Kramer, and Myths from Mesopotamia by Stephanie Dalley. Family tree of Sumerian Gods Let us start with a family tree of Sumerian gods (taken from "Inanna"):  We see some evidence of astrotheology here, I have circled the main elements: the Moon gods Nanna and Ningal, and the Sun god Utu, Inanna's brother. Inanna herself is identified with the morning and evening star (Venus). There is also a sky god, An. The astrotheological elements do not seem to be an overarching theme, though. They occur fairly low in the tree. Usual role of Sun and Moon As a short diversion, an interesting point is that in this case the Sun is the child of the Moon. Often in mythology, the Moon is the symbol of life in its cycle-of-nature aspect: in order for you to live, something else has to die--the plants or animals you eat. When you die, you get cycled back into nature as well, and more life will spring from your dead body, if only starting with maggots. The moon symbolizes this via its waxing and waning. It too "dies" only the rise again for a new cycle of its life. The Moon thus also symbolizes Life and Death as two sides of the same coin. The Sun on the other hand often is seen as symbolizing life in its constant aspect: life will proceed, unchanged, just as the Sun rises again each day, its shape unchanged. The Sun is more fierce than the Moon. Certainly in a climate like the Mesopotamian it can easily kill you. The Moon is more friendly to life, it is associated with the morning dew, which in drier climates is an important source of irrigation. The Moon is therefore often (but certainly not always) seen as female (which is also suggested by its close association with the rhythm of the womb), the Sun as male. We see something of this in the Sumerian tree of Gods. Inanna is the queen of life and the goddess of love, and she is the daughter of the Moon, if not the Moon herself. She, the female principle of life, does end up on the same "level" as the male principle of life, her brother Utu the Sun god. Inanna and Enki: the transfer of the principles of civilization I will now in a nutshell review three myths about Inanna to see how the element of astrotheology figures in them. First the myth where Inanna liberates the principles of civilization, called Me's (pr: may's) from the god of Wisdom, Enki. These Me's are things like priesthood, kingship, shepherdship, woodworking etc. Oh, and Descent to the underworld, Ascent from the underworld, The art of lovemaking, The kissing of the phallus and The art of prostitution. The first two I mention because we will see them in another myth, the others just out of generalized prurient interest. In order to get the Me's from Enki Inanna gets Enki drunk, in which state he generously gives them all to his lovely (grand)daughter. Inanna then makes a hasty getaway while Enki is still drunk, loading all the Me's into her Boat of Heaven and setting course for Uruk, her city. When Enki sobers up he tries to get the Me's back, but fails to do so. In the end he resigns himself to the situation, and thus the principles of civilization end up in the hands of the people. In other words, civilization was born to the people via an act of fertilization by the goddess of love and life. The element of astrotheology seems to be mostly lacking here. The emphasis is on the development of civilization and the role the gods of life and wisdom played in its development. Inanna's courtship The next myth is that of Inanna's marriage to Dumuzi. Inanna is still unmarried and her brother Utu decides to do something about that. He proposes as a husband the shepherd Dumuzi. Inanna answers [Inanna, p33]: What we see here is the old rivalry between agriculture and animal husbandry. We also find this in the story of Cain (a tiller of the ground) and Abel (a keeper of sheep), in Genesis. The Hebrews were shepherds, so in that story the bad farmer, Cain, kills the good shepherd Abel. In the Sumerian version things end more amicably: Inanna is convinced to marry Dumuzi the shepherd even though she likes farmers. There is probably a bit of a just-so story here: How come we should like both farmers and shepherds. Again, in this myth the focus is not on astrotheology. Rather it is about life and its procreation (getting married), its maintenance (by food from both farming and shepherding), and on the social relations between farmers and shepherds. Inanna's Descent to the Underworld The last Inanna myth I want to consider is her Descent to the Underworld. This is a quite complex myth which prefigures quite a bit of Western mythology (it's origin is in the third millennium BCE, if not earlier). I can only skim the surface here. Inanna, the goddess of Heaven and Life, decides she has to descend to the Underworld, the realm of Death ruled by her older sister Ereshkigal (the tree doesn't show her as a sister, the myth does though). Upon arrival there she tries to take Ereshkigal's place. Ereshkigal is not impressed and kills Inanna. This causes Ereshkigal to get sick: life and death, Inanna and Ereshkigal, are two sides of the same coin, and you cannot kill half of yourself without the other half sustaining serious damage as well. This gives Enki an opportunity to save Inanna. He sends some magical beings to visit Ereshkigal on her sickbed and sympathize with her sickness. Out of gratitude Ereshkigal promises her visitors a gift of their choice, and they choose the corpse of Inanna, which they then revive with some magical stuff that Enki gave them. Inanna can then leave the underworld, but she has to provide a substitute. This substitute proves to be her hubby Dumuzi, who by now is also the God of Grain. Dumuzi organizes things such that for half the year he can alternate with his sister Geshtinanna. If you are familiar with the myth about Ceres and Persephone you will recognize at least part of what is going on: a just-so story about how grain only grows for half the year, in the other half it is "dead," like its god Dumuzi who during the "dead" season resides in the underworld. Another aspect is the unity of life and death: only after Inanna has gone to the Underworld, after Life has united with Death, can the cycle of nature, symbolized by the yearly crop cycle, start. There is some astrotheology here, the yearly crop cycle is linked to the Sun for one thing. Also it is only after Inanna is gone for three days that Enki sends his rescuers. These three days correspond to the three days that the new moon is invisible. But the astrotheological aspect is secondary. Primary is the cycle of life. Atrahasis: Creation of Humanity and the Flood I'll now move from Sumerian mythology (roughly 3500-2000 BCE) to Babylonian mythology, roughly 2000-500 BCE. Of the myths I want to mention, the first is the story of Atrahasis. This myth starts as follows [Myths from Mesopotamia, p9]: The gods decided to do something about this, and they created humanity so that they could do the work. Humanity is created from clay mixed with the blood of a god slain for that purpose (Ilawela). For good measure, the gods also spit upon the clay from which humanity is created. But once humanity is created, it gets out of hand: way too many people spring up and they are way to noisy. The gods then embark on a series of campaigns where they try to kill off humanity by various means (plagues, starvation), but a few always survive to start the whole thing again (mostly due to intervention by Enki). The last extermination campaign is the Flood, which humanity survives because Enki tells Atrahasis, the Babylonian Noah, to build an ark. Astrotheology seems to be as good as absent here. Gilgamesh You can find a summary of Gilgamesh here. There is some astrotheology in the myth, but mostly in the form of the conflict between the solar (stern, rough, male) and lunar (gentile, nourishing, female) aspects of life. Gilgamesh, who is a favorite of the Sun god Shamash, stands for the solar aspect of life that has gotten out of hand. The following is from Gilgamesh by Stephen Mitchell [p73]: Anu then decides to "tame" Gilgamesh by creating a friend, Enkidu, for him. Where the Solar Gilgamesh in a sense is "above" nature, and hence abuses is, Enkidu is drawn from nature [p75]: So Enkidu is more closely connected to earthly nature, where the cycle of life and death reigns supreme, and hence is more Lunar in his nature. Enkidu is then "civilized" via intercourse with the temple prostitute Shamhat (remember that prostitution is one of the Me's). Enkidu's taming of Gilgamesh meets with mixed results. He manages to stop him from harassing his people, and Gilgamesh's attention then fixes on taming nature: he goes to the "Cedar Forest" in order to slay Humbaba, the elemental spirit of nature. Nature thus tamed, our heroes fashion a door from some Cedar trees. Compare this to the liberation of the Me's from Enki by Inanna. So far so good, but then Ishtar (=Inanna), the daughter of the Moon, has a proposition [p130]: In other words, a final union between the Solar and Lunar principles is proposed. Gilgamesh is not ready for this and refuses [p133]: (The last line refers to a rite where the women yearly bewail the loss of Dumuzi to the Underworld.) In other words, Gilgamesh is not ready to accept that he is part of the cycle of nature (as Dumuzi was), and he rejects Inanna. Inanna does not take rejection lightly and takes revenge by releasing the Bull of Heaven onto the countryside. Gilgamesh and Enkidu kill the Bull of Heaven [p138]: So, the heart of the animal sent down by the daughter of the Moon gets sacrificed to the Sun, talk about driving home a point (the bull is generally a Lunar animal as its horns resemble the crescent Moon). Ishtar does not take this well [p138]: A "thigh" is often a euphemism for a testicle, so after first driving home the point with the sacrifice of the heart, Enkidu now hammers it in with a sledge-hammer. This was a really bad idea on his part. The principles of nature can only be opposed so far, and the gods now decide to kill Enkidu. This causes Gilgamesh great grief, and causes him to embark on an equivalent of 40 days in the desert: he goes on a quest to find immortality. Of course immortality--to the extent it is possible--had already been offered him in the union with Ishtar, which he rejected. So obviously this quest will fail, but at least Gilgamesh will finally learn his lesson. The secret of immortality resides with Utnapishtim (=Atrahasis). To reach Utnapishtim, Gilgamesh has to pass through the tunnel which the Sun uses at night to return from West to East. Gilgamesh waits at the East end, where the Sun rises, and enters the tunnel just as the Sun has popped out. He then runs like mad and makes it to the other side just in time. Here we have another bit of astrotheology, but mostly with mystical, not literal, intent. Gilgamesh has to follow the path of the Sun in the reverse direction in order to reach his goal. Where the Sun goes forward, he has to go backwards, in other words he has to release his solar aspects in order to make progress. The final hurdle is that Gilgamesh has to cross the "Waters of Death" before he reaches Utnapishtim. Compare this to Inanna's descent to the Underworld, where she has to die before she can reach her full potential, symbolized by the yearly crop cycle. When Gilgamesh reaches the yonder shore (an often seen allegory for reaching "enlightenment"), he finds Utnapishtim, who reluctantly tells him how to find the plant of eternal youth: he has to dive for it to the bottom of the Great Deep. Gilgamesh does this, and starts back on his return journey to Uruk. On the way he takes a nap, a snake slithers up to him and makes off with the plant of immortality. The snake, who sheds its skin in order to become a "brand new" snake, symbolizes the cycle of life and is thus a Lunar animal: Ishtar, the goddess of the cycle of life, has the last laugh. Seeing this latest setback Gilgamesh now finally learns his lesson: he is a human, not a god, immortality is not for him. He resigns himself to his humanity and becomes a good king of Uruk. So far Gilgamesh. Although we do see quite a bit of Solar-Lunar imagery here, it is usually not explicit (Gilgamesh's relation with Shamash being the exception). What is primary in this myth is the tension between the two aspects of life: the Solar and the Lunar, but the emphasis is in life, not on astrotheology. As any good myth does, this one tells you something about both the external world (nature), and how to live with it, and about the internal world (yourself) and how to live with that. Astrotheology, to the extent it is present, plays second fiddle to that. Enuma Elish, the Epic of Creation This posting is already long enough, so I'll be short. I'll quote Staphanie Dalley's introduction to the myth: Quote:

So how much astrotheology is there? Here are the first lines [p233]: This started everything. Apsu is the domain of sweet water underneath the earth, Tiamat is the salt seawater. This does not sound like astrotheology: no heavenly bodies in sight. Most of the myth relates how Marduk slays Tiamat, who was seen as having become evil (this may stand for a new batch of gods superseding an old one, like the Olympians superseded the Titans). Is Marduk in any way astrotheological? From Wikipedia: "Marduk's original character is obscure but he was later on connected with water, vegetation, judgement, and white magic. He was also regarded as the son of Ea (Sumerian Enki) and the heir of An, but whatever special traits Marduk may have had were overshadowed by the political development through which the Euphrates valley passed and which led to imbuing him with traits belonging to gods who at an earlier period were recognized as the heads of the pantheon. There are particularly two gods — Ea and Enlil — whose powers and attributes pass over to Marduk." Ea was a water god, Enlil an air god--not much astrotheology here. There is some astrotheology, though. For example, tablet V begins as follows [p255]: Neberu/Niberu is, going by Wikipedia, Jupiter. So maybe the stands of the important gods are planets. In any case, the development of the astrotheological elements by Marduk is not exactly an overarching theme in the myth: it happens as one of many things. Conclusion I would conclude from all this that while aspects of astrotheology are certainly present in Mesopotamian mythology, they are not an overarching theme. One can certainly not say that either the Sumerians or Babylonians were Sun-worshipers. Their mythology seems more concerned with life and the principles of civilization and with nature in general, than with for example the Sun in particular. I would suggest that we see a similar situation in Greco-Roman mythology, in Celtic mythology to the extent we know it, and in Nordic mythology. Perhaps someone would care to comment on these three? The very little I know of the Ugaritic texts seems to suggest something similar, perhaps someone who actually knows them can comment on these? Gerard Stafleu |

|

|

|

|

|

#2 |

|

Regular Member

Join Date: Jul 2004

Location: Texas

Posts: 430

|

I think too little emphasis is placed on the cyclical nature of astronomical events and the allegories it offers for earthly (human?) cycles. The circle of life for instance. As opposed to the actual bodies themselves. For instance, the sun alone does not make a day, and the moon alone does not make a (lunar) month. Its the cyclical nature that is reflected in the concept.

Once again Gerard, excellent post. |

|

|

|

|

#3 |

|

Junior Member

Join Date: Sep 2007

Location: Iowa City, IA, USA

Posts: 50

|

gstafleu,

I think you're using too narrow of a definition of astrotheology. You seem to think its limited to gods that directly represent the sun, moon, or planets. You say that the Mesopotamians were worshipping nature in general and not primarily the sky. Yes, maybe true in a sense, but the two can't be separated. The seasons are based on the sun. The tide and women's menstrual cycles are based on the moon. The life cycles of animals and plants are influenced by all of this. So, its a bit simplistic to just say: "okay, there is a sun god and there is a moon god." Deities often represented multiple things simultaneously, and over time deities blended into eachother or took over eachother's traits. Also, Egypt has multiple gods that represent different aspects of the sun and I'd guess that'd likely be the same for the Mesopotamians. |

|

|

|

|

#4 | ||

|

Junior Member

Join Date: Sep 2007

Location: Iowa City, IA, USA

Posts: 50

|

Mesopotamian astronomy and astrology from the University of Utrecht

http://www.phys.uu.nl/~vgent/babylon/babybibl.htm Astrology and Religion Among the Greeks and Romans http://www.sacred-texts.com/astro/argr/index.htm Quote:

http://www.pantheon.org/articles/i/inanna.html Quote:

|

||

|

|

|

|

#5 |

|

Contributor

Join Date: Mar 2006

Location: Falls Creek, Oz.

Posts: 11,192

|

Nice collation Gerard,

It serves to establish that the notions about this thing called "astrotheology" have an associated chronology outside of the standard focus of BC&H. As a remnant in todays 21st century the 12 signs of the zodiac are some form of foundational "astrotheology" in the very primitive and foundational sense, since this was a means whereby the ancients divided the sky. Any treatment of this thing called "astrotheology" needs IMO to make mention of and then integrate these images of the sky and explain why and how these emerged from different cultures, etc. While I enjoyed reading the work above Gerard, IMO it must make refence to this thing we all know today as the zodiac and its division and its precession. Its animalistic presentations are not inaccurate in describing the actions of man, even in this so-called modern age. The stars are the stars, and the zodiac is part of our history of ideation. Best wishes, Pete Brown |

|

|

|

|

#6 | ||

|

Veteran Member

Join Date: Jan 2006

Location: London, Ontario, Canada

Posts: 1,719

|

Quote:

Quote:

BTW, I certainly agree that the Sumerians and Babylonians had a quite good grasp of Astronomy and its mathematical aspects. In the larger scheme of things, once civilization started to develop and people had time to look up from their ground-grubbing activities of continuous food-gathering towards the sky, they were without a doubt strongly influenced by the order they found there--as opposed to the general chaos that was to be found on earth. As a result the gods moved from the earth up into the sky, which in turn resulted in a need to build stairways to heaven, the ziggurats, because one needed to keep in touch with the gods. So yes, astrotheology definitely forms a backdrop to all post-paleolithic mythologies. However, as the myths show, the more earth-bound concerns remained in the foreground. It was only with monotheistic Judaism (and perhaps with dualistic Zoroastrianism before that) that the primary focus of the mythology moved into the heavens. Which had rather disastrous results, as contact between the god and his people was now lost, and hence had to be reestablished. Either by the work-around of an excessive set of earthly rules and regulations, the Mosaic law, or by the god sending a bit of himself down to earth in order to "save" the out-of-contact people from their isolation. But that's a different story. It would certainly be interesting to see a mythology whose primary, foreground, focus was on the sun, the moon and/or the stars. Maybe the Aztecs? I just don't know enough about them. BTW, just to show I'm not "hostile" to the ideas of astrotheology in general, here is a picture I posted some time ago, showing its presence in Christianity  : : Gerard Stafleu |

||

|

|

|

|

#7 | ||

|

Veteran Member

Join Date: Jan 2006

Location: London, Ontario, Canada

Posts: 1,719

|

Quote:

While it seems that precession has been known for quite some time, are there any indications it played a role of any importance in the mythology? Its influence on day-to-day affairs on earth is rather small, isn't it? Mind you, I'm not saying it doesn't exist, I'd just like to see some myth in which it played a role of any importance. For example, the position of the Sun at the vernal equinox moved into the sign of Aquarius at roughly the time of Christ. So, two questions:

Gerard Stafleu |

||

|

|

|

|

#8 |

|

Contributor

Join Date: Mar 2003

Location: London UK

Posts: 16,024

|

|

|

|

|

|

#9 | |

|

Contributor

Join Date: Mar 2003

Location: London UK

Posts: 16,024

|

Quote:

http://www.parentcompany.com/awareness_of_god/doc5.htm |

|

|

|

|

|

#10 | |||||||

|

Contributor

Join Date: Mar 2006

Location: Falls Creek, Oz.

Posts: 11,192

|

Quote:

dated thousands of years wayback in the period BCE. The tradition of astrology has been around a long time. Your question begs a study of the history of astrology, and this is a multi-threaded history, passed back and forward between a number of cultures. Quote:

off on the wrong foot. Do you intend to search through various "myths" and leave the history aside? Have a look at the problems faced by Julius Caesar in his calendar reform, where the now-in-use "Julian calendar" of 365.25 days was implemented for the first time. A large number of days were "set aside" that year, far more than the 8 days set aside by Pope Gregory in the 16th century. The calendar and the stars are related, but have their own separate issues by which they are tracked. I have not made any great study of the history of the calendar or of astrology, but I'd envisage there would be much material available related to this subject "astrotheology". (in some manner) Quote:

being born. Personally, I dont think he appeared in print until the fourth century. Quote:

Quote:

say that the "council" was called on two accounts: 1) On account of the words of Arius (we've been through these), and 2) on account of the date of "easter". These guys did not have atomic clocks and the Hubble telescope. They were always trying to re-calibrate their seasons to their festivals, by the use of the stars. It was important for them to be able to determine the equinoxes, but they had a problem due to this slowly backwards moving motion caused by precession that was only noticeable by the comparision of measurements taken over perhaps hundreds of years (the rate of 1 degree each 130 years approx). Every little while things began to be "noticeably out". I know of no calendar reforms between JC 45 BCE and Constantine in 325 (who chained "Easter" to vernal equinox") Astrology is an old word and would appear to incorporate the notions related to "astrotheology". Although I neither support or critique astrology, I have examined its principles and have noted that it has a very specific "mythological aspect" -- in that the western astrology, reliant upon calculations from the "tropical zodiac" are presently about 25 degrees in variance to the actual physical locations of the stars and planets as represented by the "sidereal zodiac". If I were to make a comment about astrotheology, then the introduction of christianity in the fourth century as the state religion seems to correspond to the epoch in which the knowledge of the precession was no longer maintained. The tropic zodiac as used by the bulk of western astrological horoscopes, etc, is essentially a map of the constellations of the zodiac as they were in the fourth century. A static rendition which will never change!!! A false picture of reality in that the stars have moved on in the last 1700 years by 25 degrees, but the traditional western astrological zodiac has remained frozen by THEOS. This is a strange state of affairs, and I would like to think that any rambling discussions about what astrotheology is and is not would include mention of these things. What would the difference be between Astrotheology and Astrology in terms of a working definition? Best wishes, Pete Brown |

|||||||

|

|

| Thread Tools | Search this Thread |

|