|

Freethought & Rationalism ArchiveThe archives are read only. |

|

|

#31 | |

|

Veteran Member

Join Date: Jul 2002

Location: East Coast. Australia.

Posts: 5,455

|

Quote:

Unfortunately they have now gone horribly wrong and become death machines. Imagine the first post fall depressed insect hovering in for his hug and a theraputic chat ("Doctor, ever since the woman ate that fucking plum, I suddenly feel the urge to use my massive sharp rostrum to peirce my neighbors exoskeleton and suck out his innards"), and he gets digested alive instead. Praise be! |

|

|

|

|

|

#32 | |

|

Veteran Member

Join Date: Jun 2001

Location: Denver, CO, USA

Posts: 9,747

|

Quote:

theyeti |

|

|

|

|

|

#33 | |||||

|

Senior Member

Join Date: Jan 2002

Location: California

Posts: 646

|

Quote:

Quote:

We shouldn't be too hard on Linnaeus however, it appears that he did recognize the VFT as something special: <a href="http://30.1911encyclopedia.org/V/VE/VERA_A_.htm" target="_blank">source</a> Quote:

And he was not alone; many early naturalists missed or misinterpreted carnivory in plants: (Juniper et al., p. 12) Quote:

I'm doing a writeup of the evolution of carnivorous plants, so I've got the refs handy. Some new stuff that turned up on a web search: <a href="http://bestcarnivorousplants.com/aldrovanda/papers_online/Fossil.htm" target="_blank">Fossil seed and pollen record of Aldrovanda</a> <a href="http://www.bestcarnivorousplants.com/" target="_blank">More C.P. Newsletter articles</a> J.D. Hooker on Darwin's Insectivorous Plants: <a href="http://www.jdhooker.org.uk/" target="_blank">Address of Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker, C.B., K.C.S.I. The President, Delivered at The Anniversary Meeting of The Royal Society, on Saturday, November 30, 1878.</a> Good pics and recent discoveries concerning the in-again, out-again sorta-carnivore Roridula: <a href="http://www.calacademy.org/calwild/sum98/plant.htm" target="_blank">http://www.calacademy.org/calwild/sum98/plant.htm</a> Obscure tidbits on Linnaeus, Darwin, and Dionaea: <a href="http://www.math.auckland.ac.nz/~waldron/NZCPS/Auckland-newsbriefs/12.4.html" target="_blank">Origin of the "steel trap" analogy for VFTs</a> <a href="http://www.dickinson.edu/~nicholsa/Romnat/dartrap.htm" target="_blank">Erasmus Darwin on the VFT</a> <a href="http://www.rc.umd.edu/praxis/ecology/nichols/nichols_notes.html" target="_blank">Some stuff on sex and botany for Linnaeus and Darwin</a> Looks like Linnaeus didn't get Aldrovanda right, either -- whereas Darwin just got himself confirmed by 21st-century science (although this article overplays it a bit): Quote:

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

#34 |

|

Senior Member

Join Date: Jan 2002

Location: California

Posts: 646

|

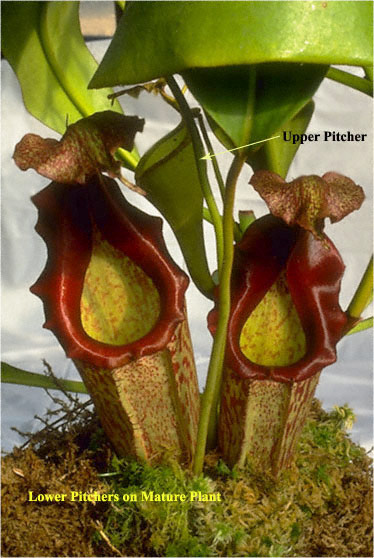

I was reading the carnivorous plants book Savage Garden by D'Amato and came across a pic of a weird-looking Nepenthes pitcher of Nepenthes infundibuliformis, aka N. eymai.

Strangely the pitcher was much simpler than your average Nepenthes pitcher, and furthermore was described as basically being a funnel with *sticky* (rather than slippery) sides. The sticky juices accumulated as a kind of sticky syrup in the bottom of the funnel. Here is a typical Nepenthes pitcher (actually, just the lower pitcher of N. eymai -- most Nepenthes are dimorphic with different-looking lower pitchers (for ground/crawling insects) and upper pitchers (for flying insects)):  (this is a potted version of the plant, actually there is an upper pitcher in the background) Another version: But here is the upper pitcher:  (source page) Why I am making this random post: The significance of this comes from recent phylogenetic evidence that most pitcher-plants appear to have adhesive-trap carnivorous plants as either basal (as with Nepenthes) or sister (as with Sarraceniales) groups. The question of how a sticky-trap could convert to a pitfall trap has not, AFAIK, actually been addressed in any literature anywhere. Pinguicula gave some hints, they are adhesive traps but many of them display significant rolled-up morphology:  ...but the upper pitcher of Nepenthes eymai would appear to give another analogous intermediate. I have no idea if there is any phylogenetic sequencing done on Nepenthes eymai yet, in general there appears to be very little info. about the plant available, so this pitcher form could just as well be derived as basal. But either way it does show the possibility of a transitional stage. At the other end of the scale, here is an "advanced" pitcher form: ...must give them bugs nightmares. PS: Here is a somewhat-closely related vine that is only carnivorous (sticky glands on the tendrils) for part of its lifetime, during the juvenile growth phase. Most online pictures suck because in the wild it is a 100-foot long tropical vine (endangered, BTW) and it does very poorly in cultivation (no reproduction or, usually, carnivory). We now return you to your regularly scheduled evo-creo debating... PPS: This thread appears somewhat messed up, the tags are appearing in the previous posts. This was occurring before this latest post BTW. |

|

|

|

|

#35 |

|

Contributor

Join Date: Jan 2001

Location: Barrayar

Posts: 11,866

|

Nic! Great post!

What's the name of the carnivorous vine? |

|

|

|

|

#36 | |

|

Veteran

Join Date: Aug 2001

Location: Snyder,Texas,USA

Posts: 4,411

|

Quote:

|

|

|

|

|

|

#37 | |

|

Regular Member

Join Date: Mar 2002

Location: Nacogdoches, Texas

Posts: 260

|

Quote:

I just visited Peter D'Amato's nursery ("California Carnivores") last week, and WOW, was it impressive! I bought a Cape Sundew (Drosera capensis), a bladderwort (Utricularia livida) and a Purple Pitcher plant (Sarracenia purpurea). They're not as dramatic as those in your pictures, but beautiful nonetheless. Makes me want to get back into systematics. (D'Amato's discussion of evolution in his book leaves a lot to be desired, but what're you gonna do?) |

|

|

|

|

|

#38 |

|

Senior Member

Join Date: Jan 2002

Location: California

Posts: 646

|

To various people:

The vine is Triphyophyllum peltatum, from West Africa. Where is California carnivores, anyhow? I saw the address but I never got around to figuring out if it was northern California or what. Tom, actually I did a paper for a class on CP evolution, give me an email and I will send it to you, I think it should have a future somewhere although I haven't been able to work on it this quarter. D'Amato is not a serious thinker on the evolutionary side of things, although his book has lots of nice pics. nic |

|

|

|

|

#39 | |||

|

Senior Member

Join Date: Jan 2002

Location: California

Posts: 646

|

Bump. Weird, I added some new notes on this topic to the thread in my bookmark, but that was on an old version of the thread, located here:

http://www.iidb.org/cgi-bin/ultimate...&f=58&t=000967 (...which has the original formatting for the old posts which is nice) Anyway I just wanted to post some articles that came up as "related" to a carnivorous plants article. ===== Quote:

Quote:

Quote:

|

|||

|

|

|

|

#40 | |

|

Regular Member

Join Date: Mar 2003

Location: 9 Zodiac Circle

Posts: 163

|

[QUOTE]Originally posted by Kosh

Quote:

1) argumentum ab inscientiae (connotations of ignorance and inexperience) 2) argumentum ab inscitiae (connotations of ignorance, na�vet� (or naivety ;) and lack of skill) I don't have much to add to the actual discussion, but since I'm much more versed in Latin than biology, no harm in clarifying things a bit. -Chiron For future Latin needs, try http://www.nd.edu/~archives/latgramm.htm and http://catholic.archives.nd.edu/cgi-bin/lookdown.pl Use the first to translate from Latin to English, and the second to translate English to Latin. |

|

|

|

| Thread Tools | Search this Thread |

|